The Walnut You Never Knew

by Wayne van Zwoll

Once as common on rifles as black on Model Ts, walnut is going the way of hickory wheels. Here’s why.

“I just paid $2,250 for a blank! Not long ago our finished rifles sold for that!” The walnut Roger Biesen bought on the eve of his retirement a few years ago was no better, structurally, than wood he had seen his father, Alvin, work up for custom rifles in the 1960s. And by many standards no more comely! Al, who’d earned celebrity building custom rifles for Jack O’Connor, told me before his death in 2016 that he’d bought most of his walnut from Sacramento supplier Joe Oakley. After Joe died, he and Roger shifted their business to Ed Preslik, also in California, then to his son Jim.

In my youth, a semi-inletted stock blank of figured American walnut could be had for $25. I paid $7.50 for a plain blank from Herters, the Waseca, Minnesota mail-order firm whose telephone-thick wish-books found their way into the school desks of young lads like me. After a winter’s labors, the walnut I’d not whittled away still resembled, vaguely, a rifle-stock. I installed it on a Short Magazine Lee Enfield that had cost me $30. Another 10 bucks snared a pair of Williams sights. My first deer rifle had left me darned near broke. A $5 box of .303 cartridges would have to wait.

Since those days of 15-cent ice cream cones and 20-cent gasoline, prices for walnut have tracked dwindling supplies. Cheaper woods like birch and beech have replaced walnut on entry-level rifles. More appealing to some shooters are laminates. Heavier, they offer greater strength and stability. Imaginatively colored, laminate stocks have appeared on some top-tier rifles too. For the cosmetically conscious there’s another option: stocks with figured, naturally finished walnut slabs that from the side conceal a laminated core. These make good use of planks too thin for one-piece stocks.

No doubt to early rifle-makers the supply of walnut seemed inexhaustible. During the 19th century such illusion erased from North America many natural resources – from the old-growth pine forests of the upper Midwest where I teethed, to stands of virgin redwoods in California and Sitka spruce farther north. In a few decades hungry saws chewed through wood hundreds of years in the making. Walnut was ideal for fashioning gun-stocks. It was hard, but easier to work than oak, also lighter in weight and not as apt to shatter. Walnut had more pleasing color and figure than hickory. Quilted maple was prized, but it wasn’t common, and its pallor begged a stain.

As the frontier moved west, so did demand for walnut. After the Great War, Edward Cox Bishop saw a future in that market. In 1929, on the eve of the Depression, he moved to Warsaw, Missouri and with son John built a sawmill. His first stocks went to Remington for shotguns. In 1935 he began turning out semi-finished rifle-stocks. Four years later Bishop invited Reinhard Fajen of nearby Stover to join his company. Fajen custom-finished stocks for Bishop. Though WW II took the men in different directions, both returned to working with walnut.

In 1949 John Bishop, who’d acquired his father’s interest in the business, suggested to Reinhard Fajen that they merge. They did, for a couple of years; then Bishop sold out to Jack Pohl, a relative. Fajen started his own company and by the 1990s had 80 employees producing stocks for 200 models of shotguns and rifles. Warsaw had become the walnut capital of the country! Larry Potterfield bought the Reinhard Fajen Gunstock Company in 1992. Three years later, having started work on a sophisticated new wood factory in Lincoln, just north of Warsaw, Potterfield acquired Bishop too. Alas, demand failed to keep this stock-making venture alive; it closed down in 1998.

Any gun enthusiast growing up in the sunny pre-Vietnam years fondly recalls Bishop and Fajen!

Time has clouded our view of the 13th century, when Marco Polo allegedly brought walnuts from their native Persia to Italy. Nuts and seedlings found their way north to Continental Europe and England. Though Juglans regia, or “royal walnut” varies in grain structure and color by region, it carries that same scientific name world-wide. Common names indicate regions, not genetic disparity. English and French walnut are both J. regia. Many migrations later, across the Atlantic, it became “California English.” Most California English grown from nuts has a tawny background with black streaks, and less “marblecake” figure than England’s walnut. Classic French is commonly red or orange with black highlights. Circassian walnut (after a region in the northwest Caucasus, on the Black sea) typically has a dark, smoky character.

American or black walnut, J. nigra, was favored by German gunmakers who crafted long, elegant flintlock, then caplock rifles in their Pennsylvania shops. These defined the famous, if curiously named “Kentucky” rifle. Predominantly warm brown in color, with black veins, American walnut has relatively open pores and, on balance, is not as hard as other species. The more ruddy Claro walnut, J. hindsii, was discovered around 1840 in California. Its surface too is more open and yielding than that of high-grade French or English walnut. Claro was crossed with English to produce ornamental Bastogne walnut. Nuts from these shade trees are infertile, but Bastogne grows fast. Stock-makers like its tight, recoil-resistant grain that also checkers cleanly. Fetching color and figure have increased demand for, and the price of, Bastogne. As with J. regia, the choicest Bastogne comes from trees at least 150 years old.

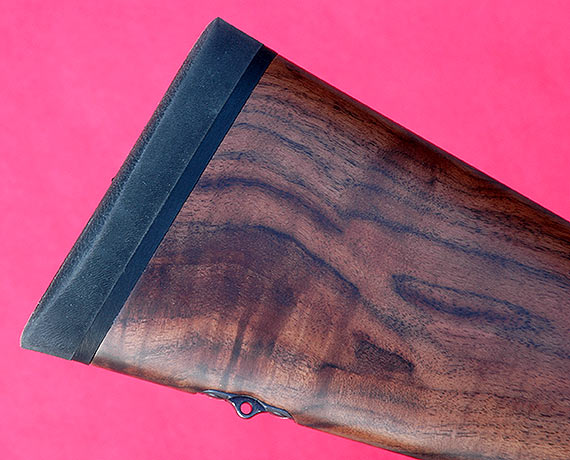

Walnut of all kinds can be plain or richly patterned, depending on the tree’s origin and age, also how it’s cut. Quarter-sawn walnut shows tight color bands, as the saw runs across growth rings. A plane-sawn blank has wider bands because the saw runs tangent to growth rings. Either cut can yield strong, handsome stocks for bolt-action rifles; but quarter-sawn walnut is a traditional favorite. Two-piece stocks for shotguns and nearly all rifles except bolt-actions are an easier assignment if you’re looking for color, figure and perfect layout, because you needn’t find a flawless blank 32 inches long.

I’ve yet to meet anyone with more walnut savvy than the late Don Allen, a commercial pilot who fashioned beautiful gun-stocks in his spare time. After building custom rifles that rivaled the best of his colleagues in that cottage industry, Don and his wife Norma established Dakota Arms in Sturgis, South Dakota. His Model 76 rifle was patterned after the pre-war Model 70 Winchester, but with better walnut, impeccably shaped, detailed and finished. Allen traveled the world to find superior walnut, later applying his talents in firearms design and stock-making to produce a Model 10 single-shot, a “baby” Sharps, and another dropping-block on the Miller action. He also fashioned an exquisite double shotgun that didn’t see commercial production.

Forty years ago, Don lamented that walnut was becoming alarmingly scarce. High-grade J. regia was already hard to find in England and France. “Fine wood comes from Turkey and Morocco,” he told me, “but even there, walnut is being felled at unsustainable rates. Some trees dropping in Turkey may be 400 years old! We’re inletting wood that predates the Declaration of Independence!” Pulp plantations grow harvestable trees in little more than a decade, but top-end walnut is the product of centuries.

Felling trees is pretty straight-forward; not so procedures thereafter. Walnut growers in France have steamed logs before cutting them into slabs (flitches). Steaming kills insects and turns white sap to amber. Before further sectioning, sawyers must also have in mind the shape and use of the final product.

Don Allen knew how to bring out walnut’s best. “Walnut must be dried before you attack it with tools,” he said. “Immediately after a blank is cut, its free water wants to escape. Think of a soaked sponge dripping. But if water leaves too fast, the wood can crack and check. Oddly enough, the surface can even crust, inhibiting further release of bound water.” A kiln throttles the drying process. He added, however, that you don’t need special facilities or equipment to bring wood gently to “safe” moisture content – just a cool, shaded place.

“After moisture content stabilizes at 20 percent or so,” Don continued, “the blank can be air- or kiln-dried without damage. Just avoid extremes of temperature and humidity, and periodically weigh the blank. When weight stabilizes, it is ready to work. Some stock-makers turn the blank to rough profile at this point, then let it dry six more months.”

Before shaping a blank, the stock must be laid out, its final shape sketched to make the most of the wood’s grain, color and figure. Viewed from the side, the grain of a quarter-sawn blank should run parallel with the grip, for maximum strength there. From above, grain in the forend should parallel the bore. While dense wood with tiny pores is preferable in all stocks, straight-grained wood perfectly laid out can be stronger and more stable than figured walnut of higher density but squirrely grain. Figure in the butt is benign; not so crotches and knots in grip and forend.

Glass bedding strengthens wood and reduces movement caused by environmental changes, but it can’t eliminate warpage. I’m sweet on glass or epoxy in the recoil lug mortise, to prevent splits in tang and magazine web and afford the lug firm, unchanging contact with the stock. A patch of glass under the tang makes sense too. Alloy pillars also ensure constant guard screw tension. While glass can be used to hide shoddy inletting, it can also complement superior work, to protect slender stocks from brutal recoil.

Checkering dresses up walnut and helps you grip the rifle. Once, all checkering was hand-cut. As hand work of all kinds became anathema to company accounts in the mid-20th century, machine-pressed panels appeared on production-line firearms. These impressions, with “diamonds” in reverse, looked as if hammered in by a meat tenderizer. Machine-cut checkering followed, and has improved.

Still requisite on fine custom rifles, hand checkering on hard, tight-grained walnut can be as fine as 32 lines per inch (lpi). Such diamonds appear mostly inside skeleton grip caps and butt-plates. Grip and forend panels wear more utilitarian diamonds. I prefer 24 lpi here, but 20- to 22-lpi checkering is more common, especially on “factory” rifles.

Most checkering panels fore and aft are variations of fleur-de-lis and point patterns. A basic fleur-de-lis is easiest because it’s a fill-in job. A point pattern incorporates the border. Minor mis-direction of the cutter inside a filled panel isn’t necessarily fatal; the flaw may be visible only on close inspection. An off-kilter line in a point pattern, however, dooms the panel! Fine ribbons and bars inside any patterns are for experts. Stock-maker Gary Goudy and others of his exceptional talent cut ribbons as slim as fly-line, uniform and clean-edged.

Long ago, I refinished gun-stocks for a shop whose brisk sales and trades sent rivers of second-hand rifles and shotguns through inventory. “Can you make bad dings go away, freshen the wood a bit, enhance the figure and make your finish look original?” asked the proprietor. “Absolutely,” I assured him.

Then the first Remington 700s and Weatherby Mark Vs landed on my bench. Their thick, shiny polyurethane finishes, essentially plastic shells applied as liquid, magnified scars. Patching with similar goop failed. I couldn’t feather old finish to produce a seamless union with new. My job then was to hand-sand all that water-proof, abrasion-resistant glitter down to the wood without scratching it. Any dishing of flat places or rounding of edges would nix an original look. Sanding behind the grip cap and up to where metal met walnut was especially tricky.

But enough whining. Hardship is relative. I was blessed too with stocks finished in varnish and oil, and a few with finishes worn and weathered off.

Oil finishes lend themselves to renewal and minor repair without full refinishing. “Oil” doesn’t refer to petroleum oil; it’s shorthand for plant-based products like tung oil (from the pressed seeds of tung tree nuts) and linseed oil. These oils dry or polymerize in air, though more slowly than you’d like. Heat-treating speeds curing; you’ll want boiled – not raw – linseed oil. Commercial oil finishes, like George Bros. (GB) Lin-Speed and Birchwood Casey’s Tru-Oil dry even faster than boiled linseed oil. Tung oil cures to a gloss that’s a tad harder and shinier. All can be feathered into lightly sanded surface repairs.

Custom stock-makers have famously guarded their pet finishes. Curt Crum has been forthcoming. For decades he has expertly finished the stunning walnut on David Miller rifles with Daly’s Teak Oil. (A water-thin sealer fills pores first.) A range of products and processes may be used to yield the warm sheen of a traditional oil or “London oil” finish.

Production-line rifles don’t merit the costs in time and labor of hand-applied oil finishes. Factory finishes have evolved. The first Winchester Model 70 stocks, in the late 1930s, wore a clear lacquer finish over alcohol-based stain and filler. The lacquers contained carnauba wax. Small flaws were repaired with stick shellac. As WW II drained supplies of carnauba wax, harder lacquers arrived. Unlike shellac (whose Sanskrit root referencing beetle or tree secretions pops up in both words), lacquers cure without imparting an amber hue, and are water-repellant.

Excepting polyurethanes, a chemical paint stripper will remove gun-stock finish to prep the wood for refinishing. Let the stripper curdle on the surface, then scrape or, with coarse steel wool, scrub the old finish off. Use a toothbrush with stripper to clean checkering. Then mask the checkering with tape before sanding, and leave that tape in place until after refinishing is completed.

Whether finishing, re-finishing or spot-repairing the finish on walnut gun-stocks, choose sanding grit just coarse enough to get desired results. Unless you’re re-shaping, stay with 220 or finer. Remember; you must remove sanding marks with finer paper! A sanding block (I use a hard-rubber eraser and, for curved surfaces, a section of dowel) helps you hew to the original profile. It keeps flat surfaces flat, edges sharp. Without the block, finger pressure can produce surface ripples. Un-backed sandpaper easily rides over edges, rounding them. Those edges should instead remain sharp until the very end, when you’ll blunt them slightly with a touch of very fine paper. I also leave until last all wood near where the stock meets steel. Once compromised by sandpaper, the original fit of walnut to metal is ruined!

Sand only in a well-lighted place, in sunlight when you can. Examine the stock often and closely. You want to find scratches, so they don’t first appear after you apply new finish. For final sanding, use wet-or-dry emery paper, 400-grit. Wet, it raises the grain and whiskers from the wood, as does steaming out dents with an iron over a wet rag. Dry strokes remove those hairs.

At this point, you may wish to apply stain, wiping it on evenly with a rag. Unless I must match an existing look, however, I don’t stain walnut, or even light-colored woods. On stocks to be finished with boiled linseed oil or a commercial substitute, follow the final sanding or steel wool polish with a thin coat of oil. It will show scratches missed earlier. Wipe off the oil, tend to the scratches, then rub the stock with a dry cloth and set it aside. A day later, if another inspection shows no sanding marks, and there’s no trace of oil, consider applying filler.

Unless the wood is tight-grained, I fill pores with spar varnish. It’s weather-resistant and thicker than most oils. It dries fast. More than one coat may be needed. Cutting surface buildup between coats with fine sandpaper or steel wool absolves you of work later. Once the varnish has filled pores to a shine, polish the stock with 600-grit paper. If you feel any stickiness, let it dry until there’s none.

Before applying finish, ensure the stock is dust-free and you’ve a coat-hanger dangling to receive it. Rub in boiled linseed oil until the wood gets hot under the friction of your hand. Thinning the oil with turpentine enhances its penetration in the wood, and can yield a slightly darker hue. Let the stock hang for a day. Drying time for Lin-Speed and Tru-Oil is considerably shorter. When the stock is dry, rub in more finish, polish this off with a soft cloth and let it dry again. You may wish to cut one of these early coats to wood with 600-grit paper. A slurry of rottenstone in boiled linseed oil can polish out small imperfections. Patiently add finish in very thin coats, ensuring that each is dry before adding the next.

The secret of a fine finish is multiple, very thin coats of oil. One ace stocker gave a fetching piece of walnut 25 coats! With boiled linseed oil, drying time can stretch from days to weeks and months! Push that schedule at your peril! As a last step, remove tape from checkering and brush oil lightly into it with a toothbrush. Let dry. Repeat. You’re done.

An oil finish is easy to repair. Light scratches can be rubbed away with an oiled cloth. Whichever oil you use, occasional light polish with boiled linseed oil, then a soft rag, can keep a stock looking fresh.

Beginning of the end?

Walnut had long seemed the ideal gun-stock material when after 143 years of building rifles with wood stocks, Remington announced its Nylon 66 autoloader. Between 1959 and 1990 more than a million of these 4-pound .22s with Zytel nylon stocks endured abuse from lads running trap-lines and exhibition shooters spewing bullets by the carton. With Nylon 66s, Remington salesman Tom Frye challenged Ad Topperwein’s eye-popping record on tossed 2 ¼-inch wooden blocks. During a marathon session in San Antonio in 1907, Ad had wearied several Winchester 1903s firing at 72,500 blocks. He’d drilled 71,491, including a run of 14,500 straight! Unintimidated, Frye passed the 43,725 mark with just two misses. He stopped at 100,010, having splintered all but six. The feat was less a tribute to the new rifle than to Frye’s stellar marksmanship. But Remington capitalized on it, following in 1963 with the Zytel-stocked XP-100 single-shot pistol in .221 Fireball. Walnut had a competitor.

Synthetic stocks, from polymer to fiberglass to carbon fiber, have since multiplied. They’re stable in wet weather (though not immune from expansion and contraction with temperature change). The best are quite handsome. But they lack the history, soul and individuality of walnut. Always will.

Wayne van Zwoll has published 16 books and roughly 3,000 magazine articles on firearms and hunting. Five of his most popular books are: Shooter’s Bible Guide to Rifle Ballistics ($20), Shooter’s Bible Guide to Handloading ($20), Mastering Mule Deer ($25), Mastering the Art of Long-Range Shooting ($30) and Gun Digest Shooter’s Guide to Rifles ($20). Limited numbers are available, autographed, from Wayne at 2610 Highland Drive, Bridgeport WA 98813. Please add $4 shipping.

Stay Connected

- Got a Break in the Montana Missouri Breaks

- It Took Six Days but We Finally Slipped One Past the Bears and Wolves

- No Mule Deer This Fall – Whitetail TOAD!

- An Accounting of Four Idaho Bulls (Elk)

- Arizona Deer Hunt 2019: Good Times with Great Guys

- Caught a Hornady 143 ELDX Last Night

- Cookie’s 2019 Mule Deer Photo Run

- Let’s See Some Really Big Deer

- Alaskan Moose Hunt Success!

- Take a Mauser Hunting: An Important Message From The Mauser Rescue Society!

- Welcome 16 Gauge Reloaders! Check In Here.

- Off-Hand Rifle Shooting – EXPERT Advice

- BOWHUNTING: A Wide One!