Bullet Pull

by John Barsness

“BULLET PULL” is the usual term for how much force is required for a bullet to leave the neck of the case, which can have a major effect on accuracy. If bullet pull isn’t consistent, then pressures will vary with each shot, and so will velocities.

Bullet pull can vary due to several factors, so there’s no single fix. Perhaps the most basic is making sure case necks are all the same thickness, whether through selection, lathe-turning in a case trimmer, or paying enough for very uniform brass — the reason some shooters are big fans of Lapua and Starline cases.

Uniform neck thickness helps center the bullet in the chamber, especially in bottle-necked cases, but uniform bullet pull is more important. Even when using brass with very uniform neck-thickness, accuracy will suffer due to variations in brass hardness.

My gunsmith friend Charlie Sisk ran into this recently when test-firing a rifle he’d just built for a customer. Charlie did all the normal stuff — “blueprinted” the action, installed a Lilja barrel, and bedded everything in a quality synthetic stock — but average 100-yard groups were in the 3-inch range, give or take an inch.

The scope had been proven on many other rifles, and Charlie does all test-firing on his own indoor range, so neither the scope or wind could be blamed. He tried several bullets and powder, and finally called me to brainstorm. (Stranger things have happened.) After asking a bunch of questions, including whether he’d measured neck thickness (he had), among other things I suggested annealing the brass, even though Charlie used new cases.

He’d never annealed any brass before, because he normally buys new brass in large amounts, then sells it after one firing, saving a bunch of resizing time — and time, as we all know, is money. But the brass on hand was the only brand he could find, and needed to work in this rifle. I outlined Fred Barker’s candle method, and the next day Charlie called, happy as hell, because the rifle now shot great.

So what was the deal? Annealing takes place at the end of brass production. The company’s annealing machine was probably malfunctioning, and nobody noticed, easy to do since there’s no visual way to test for variations in brass hardness. As a result bullet pull varied considerably, and the rifles scattered shots all over the target, even with all the accuracy aids Charlie throws into his rifles.

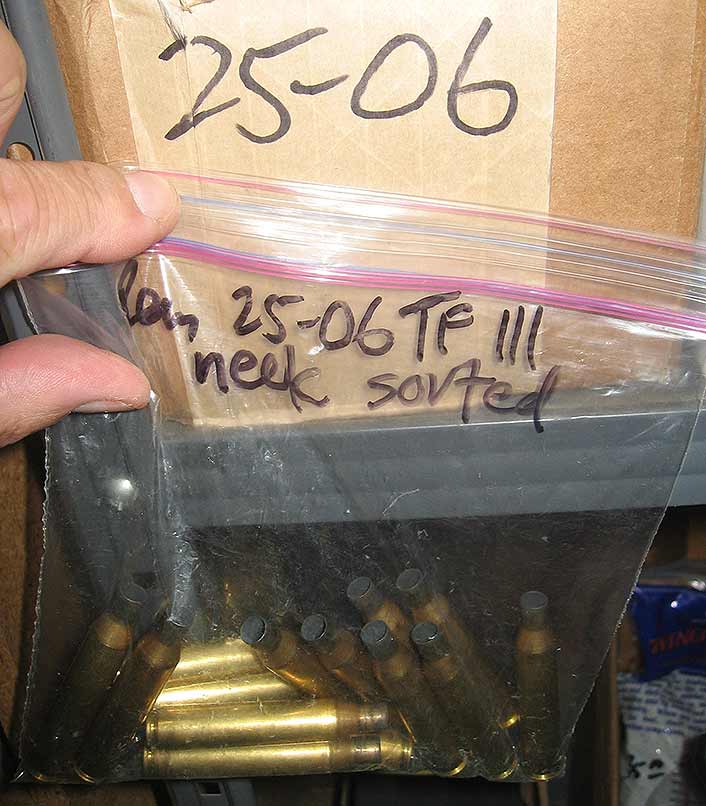

This is also why I segregate all my brass according to how many times it’s been fired. Empty cases for each cartridge are kept in plastic bags inside a box labeled “.243 Win.” or “7mm SAUM.” Each bag is Magic Markered with “Times Fired,” followed by a slash after each firing. A batch of ammo is loaded only with cases that have been fired the same number of times. Usually they’re annealed after every four firings, though the 6mm PPC cases for my benchrest rifle are annealed every time.

If you don’t want to go through all the trouble of uniforming the neck of every case, whether through selecting or turning, it helps to make sure the inside diameters of the necks are the same. This is why many shooters report finer accuracy after resizing brand-new brass, instead of just loading them straight from the bag or box — but the most important change is the inside diameter of the neck, “uniformed” by pulling the neck over an expander ball.

Unless something’s drastically wrong with new brass, I don’t bother with full-length sizing, since the factory already did the job in their case-forming dies. But I do run the necks of new cases over an expander ball — exactly what ballistic technicians do when loading new cases for piezo-electronic pressure-testing, where only new cases can be used. Or at least that’s what techs in pressure labs I’ve visited do.

Even that doesn’t eliminate pull-pull variations. In one instance, the tech commented that he could feel a variation in the force required when seating bullets in 6mm Remington cases, even after the necks had been run over an expander ball. He was sure we’d see some abnormal variations, and yes, the rounds requiring more force in seating bullets resulted in the variations he predicted. The difference wasn’t much, but it was measureable, both in PSI and velocity.

Some handloaders believe crimping the mouth of the case results in more consistent pressures, and hence finer accuracy. Well, yes, it can — but once again, crimping is only one part of the picture. Elmer Keith pointed out decades ago that a handgun case firmly gripping the bullet was more important to good accuracy than the crimp itself. He was right, but that doesn’t mean crimping won’t make any difference. One reason the Lee Factory Crimp die often helps accuracy is a reduction in bullet pull variations, essentially through taper-crimping.

When loading straight-walled cases for single-shot rifles I don’t use the mouth-crimping feature on the seating die. Instead I just seat the bullets, then run the loaded case into the sizing die with the decapping assembly. Doing this uniformly, with the same amount of pressure applied to each round, definitely helps accuracy. (Some handloaders have been known to stand on a bathroom scale when crimping necks, watching the scale to make sure they’re applying the same amount of force each time. I don’t bother, instead trusting my feel of the press handle, but hey, whatever works.)

All these principles apply to mouth-crimping, necessary in some revolver and rifle rounds. The brass should not only be annealed or fired the same number of times, but should be trimmed to a uniform length after sizing. Otherwise bullet pull will vary from shot to shot.

Some handguns and, especially, rifles react less to variations in bullet pull. Heavy-barreled varmint rifles often group pretty well despite brass that’s been fired different numbers of times, or new brass with necks that haven’t been uniformed in any way, including being run over an expander ball. But that’s because heavy-barreled varmint rifles often shoot almost any load into essentially the same point-of-impact at 100 yards. And I must confess to not being as anal about bullet pull when loading several hundred rounds for a prairie dog rifle. So what if it puts 10 shots into 1” instead of 3/4”? If I miss a prairie dog, it’s going to be due to the wind, or my lousy hold or trigger pull — and there’ll be another PD to shoot at soon anyway, maybe even the same one.

But if we want the finest accuracy, for whatever reason, it pays to make sure bullet pull is as uniform as possible, and that means uniform neck thickness, hardness and length.

John’s new book Modern Hunting Optics and other great stuff can be ordered online at www.riflesandrecipes.com.

Stay Connected

- Got a Break in the Montana Missouri Breaks

- It Took Six Days but We Finally Slipped One Past the Bears and Wolves

- No Mule Deer This Fall – Whitetail TOAD!

- An Accounting of Four Idaho Bulls (Elk)

- Arizona Deer Hunt 2019: Good Times with Great Guys

- Caught a Hornady 143 ELDX Last Night

- Cookie’s 2019 Mule Deer Photo Run

- Let’s See Some Really Big Deer

- Alaskan Moose Hunt Success!

- Take a Mauser Hunting: An Important Message From The Mauser Rescue Society!

- Welcome 16 Gauge Reloaders! Check In Here.

- Off-Hand Rifle Shooting – EXPERT Advice

- BOWHUNTING: A Wide One!